MICHAEL CURTIZ

Michael Curtiz directing Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman on the set of Casablanca

Why this site?

Though movies like The Kennel Murder Case, Mystery of the Wax Museum, The Charge of the Light Brigade, The Adventures of Robin Hood, Yankee Doodle Dandy, Casablanca & Mildred Pierce are considered genre-masterpieces, Curtiz is rarely seen as the auteur of these films because on the surface they are so radically different that it is difficult to see a connection. Also the sheer bulk of his output has made it difficult for filmcritics to label him as an auteur. It is my opinion though that by looking at his best work you can certainly find a distinct signature;stylisticly but also thematicly. Therefore the dismissal of Curtiz as merely a likeable craftsman(Andrew Sarris), does not do him justice. I recognise the fortunate position he was in working for the Warner Brothers Studios in the 30's and 40's,with people like Anton Grot,Sol Polito, George Amy, Max Steiner,& Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Little is known about this Hungarian born director. Reports about his life tend to contradict. This site is put up to share and gather information from the web about my favourite director.

FEATURED ATTRACTIONS

THE LIST OF MOVIES

Eye-candy

QUOTES

some funny and interesting quotes and of course "curtizisms"

TRIVIA

The Curtiz guest-house

RELATED LINKS PAGE

A perfect way to understand why this director doesn't get the credit he deserves is to read this bookreview:

THE CASABLANCA MAN: THE CINEMA OF MICHAEL CURTIZ

By James C. Robertson. New York: Routledge, 1995. 202 pp.

Author James C. Robertson describes himself as "an incurable but inexpert

film fan." In his book he seeks--thanks to a grant from the British

Film Academy that allowed him to study the Warner Brothers Archive-

-to set the record straight on Michael Curtiz, whose films have given

him great pleasure for many decades. In Robertson's opinion, the view

that Curtiz was a "studio hack"--or, at best, a skilled technician

who owed the visual quality of his films to his art directors and

camera-men-is unmerited. In contrast, Robertson argues,Curtiz was

undeniably the top director at Warners during the classic studio period.

He was a master of many genres, whose "distinguished record of high-

quality versatility in depth . . . no other Hollywood director can

even approach."

Of necessity, because information is skimpy, Robertson devotes only

three paragraphs to Curtiz's early career in Hungary. There are only

five more about his days in Vienna, which brought him to the attention

of Jack and Harry Warner--probably because Robertson primarily wants

to discuss the films that most of us have seen. Nine pages are devoted

to Curtiz's silent films and those in which he made the transition

to sound.  Chapter 3 examines the director's output (1930-35) as he

expanded his repertoire of genres: musicals, horror films (Dr. X and

The Mystery of the Wax Museum,The Walking Dead), detective dramas (The Kennel Murder

Case), social protest (20,000 Years in Sing Sing and Black Fury),

and adventure/spectacle (Captain Blood). Although their variability

depended on the assignments, the films of the late thirties form an

impressive list of crowd-pleasing entertainments: The Charge of the

Light Brigade, Kid Galahad, The Adventures of Robin Hood, Four Daughters,

Angels with DirtyFaces, Dodge City, The Sea Hawk, and The Sea Wolf

Robertson always takes care to remind readers of the box-office earnings

of these popular movies; and to Curtiz's advantage, his record is

compared, artistically and commercially, to that of his onetime colleague

at Warners, Mervyn LeRoy.

Chapter 3 examines the director's output (1930-35) as he

expanded his repertoire of genres: musicals, horror films (Dr. X and

The Mystery of the Wax Museum,The Walking Dead), detective dramas (The Kennel Murder

Case), social protest (20,000 Years in Sing Sing and Black Fury),

and adventure/spectacle (Captain Blood). Although their variability

depended on the assignments, the films of the late thirties form an

impressive list of crowd-pleasing entertainments: The Charge of the

Light Brigade, Kid Galahad, The Adventures of Robin Hood, Four Daughters,

Angels with DirtyFaces, Dodge City, The Sea Hawk, and The Sea Wolf

Robertson always takes care to remind readers of the box-office earnings

of these popular movies; and to Curtiz's advantage, his record is

compared, artistically and commercially, to that of his onetime colleague

at Warners, Mervyn LeRoy.

In the forties, there was more of the same, with Janie and the like

following Yankee Doodle Dandy and Casablanca. Curtiz is said to have

seen the potential of Mildred Pierce as a film noir, as if he also

anticipated the coining of the term: In keeping with his reputation

for versatility, Curtiz directed some dire projects (Night and Day)

and some prestigious ones (Mission to Moscow and Life With Father).

I would agree with the author that Curtiz's masterpiece is The Breaking

Point (1950). "Far and away the most successful serious attempt to

bring the spirit of Hemingway to the screen," this version of To Have

and Have Not stands in stark contrast to the Howard Hawks film of

that title, which relates in no way to Hemingway's novel. The film

displays Curtiz's gift for drawing superior performances from actors:

John Garfield, Patricia Neal, Phyllis Thaxter, and Juano Hernandez

were never better. I wonder, as Robertson does, why it is not available

for viewing. (It is not on video cassette, and television stations

do not schedule it.)

Robertson devotes a brief chapter to Curtiz's later career, after

he left Warner Brothers. The move was assessed by Andrew Sarris in

American Cinema as a demonstration of artistic decline when studio

discipline was lacking. Robertson disagrees, arguing that White Christmas

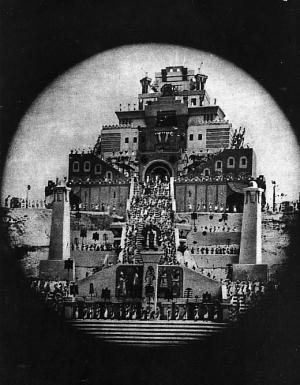

is "very good light entertainment" and that The Egyptian for "sheer

spectacle" represents Curtiz at his best. Some readers may share my

opinion that the first is unwatch-able and the second is ponderous

and dull. Curtiz also took on several doomed projects, such as The

Vagabond King with Oreste. However, Robertson makes a case for reassessments

of King Creole, The Proud Rebel, and The Best Things in Life Are Free,

although he does not convince me that virtues can be found in The

Helen Morgan Story. Because Robertson is concerned almost entirely

with Curtiz's public career, he intimates, surprisingly, that Cur-

tiz may have become involved in several woeful films because he needed

money to support the illegitimate children he allegedly fathered.

Hardly ever is what we see on the screen related to his private life.

To establish Curtiz as an auteur is difficult, but he had the ability, as in Casablanca, "to weld player, writers, and technicians into a strong team." Like John Ford, Curtiz thought that a film should be cut in the camera, and like Billy Wilder he understood that a first- rate film cannot be made without a first-rate script.

The truth probably

liessomewhere between the dismissal of Curtiz as a superb technician,

who subordinated his talents to the studio machine, and Robertson'

s somewhat idolatrous view that Curtiz's "large-scale versatility

is unique in cinema history and unlikely ever to be rivaled, much

less surpassed."; For the author, the frequency of showings of Curtiz'

s films on television is an enduring tribute to the director's talent.

In any case, Robertson's book concisely re-opens the debate about

Curtiz's contributions to cinema.

By James Van Dyck Card, Old Dominion University

Van Dyck Card, James, Book reviews.., Vol. 24, Journal of Popular Film & Television, 04-01-1996, pp 45.

When you've finished viewing my pages, be so kind to:

or if you have any comments,suggestions or questions write to me:

|

|

|